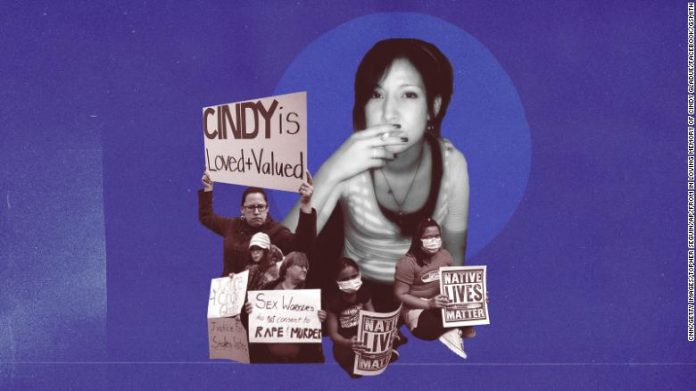

February marked the culmination of a virtually decade-long legal saga that raised federal questions about how Canada treats Native girls. Cindy Gladue, a 36-year-old Canadian Cree-Métis mother of 3, bled to death in a hotel bathtub almost a decade ago.

The jury in the six-week re-trial at Edmonton, Alberta, had discovered witness testimony which Gladue endured an 11-centimeter wound to her vaginal wall while engaging in sexual acts with Barton at a hotel in town in June 2011, based on CBC reports.

At trial, Barton testified he agreed to pay Gladue for sex and met her over two nights, also insisted it was consensual, according to the CBC. He said he didn’t realize she had been injured, and was shocked when he found her dead the following morning.

However, prosecutors argued that Gladue may have been too drunk to give approval, and drew attention to inconsistencies from Barton’s testimony.

Though the agonizing way in which Gladue died is a source of despair for her friends, family and community, the case has become a rallying cry for activists, raising questions about race and discrimination in Canada.

A questionable trial

In 2015, a jury — described as”visibly White” in CBC news reports — acquitted Barton of first-degree murder and manslaughter charges, a verdict that triggered protests across the country and sparked a debate about how Canada’s justice system treats Indigenous women. Canada’s Supreme Court agreed and ordered Barton be retried for manslaughter, noting the country’s trial principles for dealing with sexual history weren’t followed.

Many saw the first trial as disrespectful to Gladue, says Julie Kaye, a national campaign pro for Indigenous justice team Pima’tisowin e’ mimtotaman told CNN.

Kaye stated Gladue”wasn’t portrayed with individual dignity, as an individual being,” during the 2015 legal event, which she said saw prosecutors deliver a specimen of her preserved pelvic tissue into the court as evidence of the deadly wound she endured.

“They attracted a part of her body in as signs and known to part of her body for a specimen — it violates rights in terms of how we handle people’s bodies once they’re dead, also it simplifies Indigenous protocols round caring for loved ones after they have passed,” Kaye said.

According to the Globe and Mail, pictures of Gladue’s vaginal tissue — that was brought into courtroom but concealed behind a display — were projected on a screen for jurors to see. Presenting part of Gladue’s body at trial,” Kaye said,” was regarded as an extremely violent act.”

Gladue was additionally referred to as a”Native” or”prostitute” during the trial, according to the Supreme Court’s ruling in the case.

“She wasn’t all these labels, these words that they said: She had been a momma. People should have admired and admired her because she was a girl and she really loved her loved ones,” Gladue’s cousin, Prairie Adaoui told CNN.

“Each of the stereotypes and stigma associated with how she had been called and the titles used for her, that really allowed racism and sexism to input into the event,” Kaye said.

‘Canadian genocide’

For years, activists and Indigenous people in Canada have warned of a disproportionately large number of Indigenous women who have either gone missing or been killed throughout the country.

“The violence which Cindy Gladue endured needs to be located within a context [of] continuing settler-colonial relations marked by gendered violence,” said Lise Gotell, professor of womens and gender studies in the University of Alberta.

“As a consequence of colonization, cultural dislocation, and poverty, Native American women and women continue to face intense forms of marginalization, such as rates of violence that are many times those of other women,” Gotell said.

Though they represent about 4 percent of all women in Canada, Indigenous girls made up almost 28% of homicides perpetrated against women in 2019, whilst authorities estimated in 2015 that some 10% of the country’s missing women were Indigenous.

A 2014 report from Canada’s Royal Canadian Mounted Police identified 1,181 Indigenous women that had been killed or gone missing between 1980 and 2012.

Two years back, a federal enquiry explained the thousands of Indigenous women and women who’ve been killed or have disappeared in Canada in the past decades as sufferers of some “Canadian genocide. ” The report contained testimonies from more than 1,400 relatives and survivors, and 84 knowledge-keepers, officials and experts.

A national action plan was designed to follow with the report, but progress was slow. Communities are still waiting for the plan, which was due in June this past year.

Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett advised CBC News that additional work and consultation should take place prior to a proper response to the report’s recommendations can be finished, and said the pandemic had impacted the government’s timeline.

“Just how are you going to make all of these wrongs correct?

Many activists point to other high-profile incidents involving Native women who raised controversy over their treatment in Canada’s legal, health care and prison systems.

Kaye told CNN”there has been a number of distinct cases where somebody coming in touch with the system for a sufferer is treated as though they’re to blame,” she said.

Protesters gather during a demonstration in central Montreal on October 3, 2020, to need action for the death of Joyce Echaquan, a Canadian native woman exposed to live-streamed racist slurs by hospital staff before her death.

The CBC reported footage that Echaquan filmed prior to her passing — appearing to supposedly show medical staff calling her”stupid” and”only great for sex” — triggered protests in Quebec City and Montreal. The question is scheduled to begin in May 2021.

The state’s nursing body L’Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec at a statement denounced that the”racism suffered” by Echaquan. In an October video statement, Luc Mathieu, President of the OIIQ stated he had asked for a meeting with authorities in Manawan — that the Indigenous community Echaquan was out of — and is exercising a pair of disciplinary measures.

Lathieu said the nursing body will be reviewing training plans to establish if they’re sufficiently preparing future nurses to manage First Nations communities.

Based on CBC News reports, a nurse and a patient attendant at the Joliette hospital had been fired, and investigations from the local health jurisdiction have begun.

And in 2015, a sex assault victim called the pseudonym Angela Cardinal was taken into custody for five nights, transported to the courthouse at precisely the same prisoner van because her attacker, also testified while shackled — against the guy who was ultimately convicted of attacking her, according to CBC reports.

An unaffiliated investigator reviewing the case on behalf of Alberta’s Justice Minister later called the events”a comprehensive breakdown of legal protections.”

The provincial court judge who agreed with federal prosecutors to possess Cardinal remanded into custody was cleared of any judicial misconduct, based on CBC. The CBC reported that the Alberta Judicial Council determined that the judge failed to did not order that Cardinal be treated in such a way, and that there was no proof that the complainant’s sex or aboriginal status affected his decisions.

“It is a form of racism that if we look at people, to say they’re to blame because of their scenario when any other individual, in case a violent action happened, they would expect to be treated with dignity and respect,” Kaye told CNN. “And yet we don’t see that occurring for Native women”

“We have to really actively address [it] to make sure that in our trials, we’re not allowing bias against native men and women enter into those areas,” she added.

Institutional racism still pervades in the nation’s legal systems and healthcare systems,” Whitman said. In 2020, Indigenous women accounted for a 42% of Canada’s female prison population. “We need the government to listen and admit there is systemic racism in these associations,” she explained.

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau last year confessed that systemic racism, was an issue throughout the country”in all our institutions, including in all our police forces, including in the RCMP.”

“In several cases it’s not deliberate, it is not intentional, it’s not competitive, individual acts of racism, but those obviously exist. It’s recognizing the systems we have built over the previous generations haven’t always treated individuals of racialized wallpapers, of Indigenous wallpapers, fairly throughout the very construction of the systems which exist,” he said.

RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki said that racism was present at the force, including in a statement:”As many have said, I do understand that systemic racism is part of each association, the RCMP included. During our history and today, we have not always treated racialized and Indigenous people fairly.” Lucki promised”thoughtful actions” and consultation with Indigenous leaders and members of the RCMP in reaction.

‘She never had a voice’

Members of Gladue’s family say that although the verdict will permit them to start healing, 10 years after her violent death, the press coverage and lawful treatment of Gladue’s case has failed to introduce her as a human being.

“We haven’t been able to cure as victims, because the trauma sits there,” Adaoui told CNN. “Cindy has not been laid to rest yet, and I believe this is just the beginning to the recovery journey.”

“She died a violent death and it took a decade for us to have some kind of justice for her. She had a voice, and we kept revisiting these two nights. But not just that, they didn’t look in her as a person. She was a human being and that is the most important,” she added.

“She had been a person, she was a mother, she had been a daughter, she’s now a grandmother; she was a life giver,” Adaoui said. “She was a beautiful person, and I think that part was not shown.”